By: Master Coach, Tim Cusick

Base training is a hot topic these days. There has been a steady stream of articles and podcasts discussing a variety of ways to build your base and improve performance, with ideas ranging from High-Intensity Interval Training (H.I.I.T) to polarized training to different versions of high-duration, more steady-pace base building.

I’ve watched many of these approaches in practice over the years, and while each have merit, it’s hard to beat high-volume base training when it comes to targeting a higher peak in your annual training and performance strategy. The deeper your base, the harder and deeper you can train when it comes time to turn up the heat and start building toward performance and speed.

Some attendees of Velocious Cycling Adventure’s camp in Fredericksburg, Texas.

Our team at Velocious Cycling Adventures had the pleasure of working directly with our sponsor partners at PowerTap in our most recent base training camp in the Texas Hill Country of Fredericksburg, Texas. Beyond supplying us with demo power pedals, wheels, chainrings, and trainers, they loaned us Product Manager, Brian Turany, to test our base training theory on. We rarely get the opportunity to truly immerse one of our sponsors like we did here, and we had a blast.

The Challenge

Let’s lay out the challenge of a base training camp by the numbers. Since we focus on building aerobic fitness and muscular stamina, the five-day plan looks like this:

- 20-23 hours of estimated training duration

- 1,000-1,200 estimated TSS (Training Stress Score) points

- 410 scheduled training miles

- Two fatigue resistance days where the last 60-75 minutes are conducted at a higher power target

- 3 groups riding at different paces

- An easy recovery day on the sixth day

This is a pretty high training load, as you can imagine, but in my opinion, base training is not just high-volume riding at slower paces, but a blend of extensive and intensive aerobic training ranging from the classic zone 2 endurance to high tempo/sweet spot training zone 3. I also like to mix in some non-steady-state riding to further challenge the riders’ systems.

Tim digs deep into the power training data from PowerTap Product Manager, Brian Turany.

Tim digs deep into the power training data from PowerTap Product Manager, Brian Turany.

The Rider

PowerTap Product Manager, Brian Turany, is an experienced rider with a pretty big engine. Before camp began, we ran Brian's historical power data through the TrainingPeaks WKO4 power duration curve (PDC) to get an overview of Brian's unique physiology. Here's what we learned about him:

- WKO4 classified Brian's power model as that of a TTer, meaning his power duration curve was a little flatter, signaling that his real strength is in longer, steady-state riding efforts and events.

- Brian's Functional Threshold Power (FTP) peak in 2017 was around 355 watts.

- His modeled anaerobic work capacity (FRC) was 14.3 kilojoules.

- Brian's PDC-modeled VO2max was approximately 69 ml/min/kg. This is a pretty high number, and it gave us some immediate insight into Brian's capability in endurance sports. His power at VO2max is around 430 watts; that's pretty solid.

- We estimated his fiber type and learned, as expected, that he is slow-twitch dominated, which gives us a good indicator of how he makes power and more importantly, how he utilizes energy.

- Brian trained about 9-12 hours a week over the 90 days prior to camp, with some significant time on the trainer due to the cold weather in Madison, Wisconsin.

Image 1: Brian's profile in WKO4.

The Training Diary

Day 1: Getting Comfortable

Day one at our training camps is typically a longer day focused on getting the group comfortable riding with each other. This means working on some basic principles of pacelining and learning to work together. Overall this was a pretty easy day for Brian.

Take a look at his time-in-zone (TIZ) report based on Coggan Classic Training levels. Since Day 1 was a lot of instruction and slower riding, we can see that Brian accumulated a lot of time in zone 1. We'd have to make the rest of the week harder to make up for it.

Image 2: Brian's time-in-Zone (TIZ) report from Day 1.

Day 2: Testing Fatigue Resistance

Day 2 saw Brian's group working on testing fatigue resistance. A lot of riders can ride strong in the first 60-90 minutes of a ride, but the ability to resist fatigue and perform late in events is crucial to success. Today's ride goals were to burn approximately 1,500-2,000 kJs of work and then execute a 60-minute tempo paceline home.

We again used TrainingPeaks' WKO4 and Brian's historical numbers to look at his historical fatigue resistance by building unique power duration models after 2,000 kJs. We learned this might be an area of development for Brian.

Take a look at the comparison below, in figure 3. This chart shows his 2017 season power duration curve overlaid with a second curve generated after 2,000 kJs were spent. This is a unique feature of WKO4 that can give some valuable insight. Take a look at the variance in the curves and his drop-off in peak powers after 2,000 kJs.

Now, I don't have much knowledge of his training history, so it might just be that he never had the need to go hard late, but this is an area to explore, as his drop-off in both percentage and actual watts is pretty high and should be a focus of his training. It could also be related to poor on-the-bike nutritional habits.

Image 3: Comparison data mapping in WKO4.

Day 3: More Fatigue Resistance

Due to some predictions of windy weather, we switched our planned days 3 and 4, and this created a unique challenge for our campers, as it gave them two fatigue resistance days back to back.

This meant an expectation for Brian similar to day 2, but with an additional little twist: on this day, once we got our kJs in the bank, we stopped the group and assigned everyone a secret number ranging from 15-90. Once everyone had a number, the exercise for this “fast” group was a single-paceline, 25-mile, speed economy ride back home.

The single paceline was high tempo efforts and above, but each rider had to pull for the length of time corresponding with their secret number. The goal was to better blend stronger riders with the group by teaching adjusting pull length vs. power.

This tends to make things harder, because once everyone gets a good feeling for the timing, speeds tend to ramp up a little and people pull harder. One of the ways we measure the efforts of these pulls is by looking at matches—higher anaerobic efforts that tend to really drain the battery over time.

Attendees at the camp worked paceline skills.

Once we were back at the hotel, recovered, and showered, we reviewed the idea of heat mapping workouts to give riders a better visualization of just how hard they had worked.

Take a look at Brian's heat map below. As one of the stronger riders in the group, he was assigned a longer pull time of 90 seconds. You can see that he kept things well controlled heading out, but once the paceline got started, he generated some long, hard pulls but controlled his pacing perfectly. (Too much red in in a hot paceline is a recipe for disaster.)

Image 4: Brian's paceline data from Day 3.

Let's compare Brian's heat map to another group member we'll call Jim Rider. Jim was working harder in the paceline, as you can see by the high amount of red in his heat map. Over time, the fatigue of all those matches built up, and Brian was able to slip away and arrive back in town first. The exercise was not a race, but it did demonstrate that Brian's slightly more conservative approach paid off.

Image 5: For comparison, a look at paceline data from “Jim Rider”

Days 4 and 5: Long, Easy Endurance Days

Days 4 and 5 were long, easy endurance days. Our campers were now starting to feel some fatigue and learning to ride together better. The goal of day five was to run a simple progressive endurance day.

The idea of progressive endurance is simple: head out in a lower zone 2 and simply increase watts slowly over time, finishing at mid to high zone 2. We simply wanted to keep the pedals turning and hit the power training targets while enjoying the weather and the company.

Even though our campers can be pretty fatigued at this point, day five gives us insight into their aerobic fitness. One way we review this using power meter and heart rate data is by measuring cardiac drift (and we actually measured this throughout the entire week).

From Brian's chart below, we can see that even though he is pretty strong, he shows some sign of cardiac drift; we can see his heart rate trending up faster than his power, and when measured, he “drifts” about -17%. This is an indicator of lower aerobic fitness, which I would encourage focusing on in his next training cycle.

Image 6: Analyzing Brian's cardiac drift in WKO4.

Brian had to head home a day early, so we weren't able to get his day six performance, but he left happy and with plenty of great training. Take a look at a summary of his activity for the five days he joined us for:

Image 7: A snapshot of Brian's training journal from 5 days at Velocious' camp.

Time at VO2max

A unique way we track training intensity is as a percentage of VO2max, as it gives us deeper insight into the training strain.

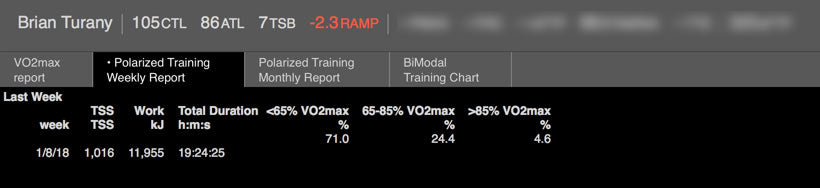

Based on his modeled VO2max, Brian's week was a solid aerobic week (71% of the time at <65% of VO2max), with some time at tempo/FTP effort (24.4% of the time >65% but <85% of VO2max) and a small amount of time higher.

Image 8: A snapshot of Brian's VO2max.

What Comes Next?

Next we rest! The timing of rest will vary based on each rider's chronic and acute training history, and resting is a fine line; you want to rest enough to trigger a super compensation response, but not so much that you don't take advantage of continuing to build fitness in the traditional base period.

Since we know that most of Brian's time was spent below 65% of his VO2max and only 4.6% of the time was spent over 85% of his VO2max, he will not need that much recovery time. Sure, he did a lot of work in the mid-zone of 65-85%, but the reality is that this was still fueled by aerobic energy and wasn't that draining.

With a high-volume week completed, I suggest he rest totally off the bike for two or three days, then begin working his way back into training.

Riders and coaches at Velocious Cycling Adventure's camp gather for a group photo.

Wrapping It Up

So the lesson for the day? Base training camps are hard, and they're not just about riding long, slow distances. By utilizing power meter and heart rate training data, we can not only provide a more individualized training dose, but also take a deeper dive into training review. As I said earlier, there are other ways to approach base training, and one of the things we preach is to use data to find the system that works best for you.

Since this was a more traditional approach for Brian, we need to track his response over time. It typically takes a person an average of four to eight weeks to adapt to training, and I have a feeling Brian will start feeling some positive effect and achieving some improved results/numbers in a month or so.

Big thanks go out to PowerTap for being such a great partner with Velocious Cycling Adventures, and to both Brian and his amazing wife, Meredith, for joining us at our Texas Hill Country Base Training Camp.

Interested in joining us for a future camp and demoing Saris products, including PowerTap power meters and CycleOps trainers, like Jan below? Check us out at Velocious Cycling Adventures.

Brian working with camper Jan Workinger.

Tim Cusick is the TrainingPeaks WKO4 Product Development Leader, specializing in data analytics and performance metrics for endurance athletes. In addition to his role with TrainingPeaks, Tim is a master coach with Velcocious Endurance Coaching.

Working primarily with professional athletes, Tim has coached multiple World and National Champions, including pros Amber Neben, Emma Grant, Adam Bucklin, Miriam Brourer, Carson Miller, Zdenek Vobecky and while also consulting for numerous professional teams. For more information on Tim, visit velociouscyclingadventures.com/velocious-coaching.